Maximizing Solar Farm Efficiency with MPPT and Current Sensing

A look at the latest trends in utility solar farm designs and how their efficiency can be improved

Trends in Utility-Scale Solar Farm Design

Large solar power farms are changing the way they work to boost efficiency so they can draw the most power from their assets.

The solar market is split into three sectors. First, is residential, the solar panels that householders have on their roofs. Second are the installations on commercial buildings. But the largest, and the ones that can most benefit from an increase in efficiency, are the utility scale plants that produce electricity in the same way as a coal-fire plant.

These plants use a central inverter system between 500kW and 2MW. From the central inverter are a number of combiner boxes and from these run the strings of solar panels themselves. These photovoltaic strings normally contain around twenty panels (and vice versa… the energy comes from the panel to the inverter).

To draw the most power from a panel, there is what is known as the maximum power point (MPP) for voltage and current, and systems to detect this are called maximum power point trackers (MPPTs). To find the MPP, the current through the panel is steadily increased until it reaches the point where the most power is being drawn. If the current is increased beyond that, the power drawn goes down again. The MPP is influenced by how much sun falls on the panel.

The way solar plants traditionally operate is they run all the panels at the same MPP. With the panels in series, the same current flows through them all. The various strings are wired in parallel with each other and all have the same voltage.

Why Uniform MPPT Reduces Efficiency in Large Solar Farms

Now, as long as all the panels are relatively similar, have the same orientation and no shading, and they can all see the sun, then running them all with the same MPP is fine.

The reality though, especially with a large solar farm, is that this is rarely the case. The sun will be hitting the panels at different intensities. For example, a cloud going over the farm will mean that some panels are in shade while others are in bright sunshine and some in between.

If the system is set up so that all the panels run from the same MPP, this is effectively the MPP of the least efficient panel and thus the efficiency of the whole plant is brought down significantly.

Zoning Solar Farms for Optimized Power Tracking

The trend therefore is to split the plants into smaller zones with each zone having its own MPPT. This means that separate areas of the plant will be running at different MPPs depending on the state of the sun.

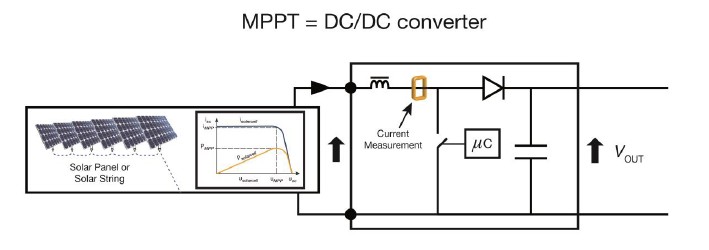

An MPPT is basically a DC-DC converter. In the past, many plant operators baulked from installing inverters with many of these because the extra costs involved outweighed the efficiency savings.

What has changed now is that the latest power electronics have reduced the cost because they can switch at a higher frequency. The switching frequency used to be around 20kHz but now it is around 50kHz, and this is likely to rise further in the future.

The higher frequency means that the size of the inductor can be reduced, making the whole system smaller and thus cheaper. It also means the IGBTs and other power components are more efficient, so they generate less heat and so need a smaller heatsink.

The Rise of String Inverters in Utility Solar Installations

Growing in popularity is to take this further and have an inverter at the end of each six to ten strings; this is the string inverter. Each string inverter is only about 30 to 50kW and this has the added advantage that if one inverter fails then only a small zone is offline while that panel is replaced. It also makes it easier to trace the faulty panel or string inverter. Once traced, these can be swapped and replaced by an on-site engineer. As spares are normally kept on site, the downtime is reduced dramatically.

Such installations can involve having as many as 200 MPPTs for each megawatt. This is slightly more expensive but the price is falling as the volume increases, and again with the improvements in power electronics. Market analysts forecast that the utilities installed with string inverters will overtake those with central inverters by 2018.

Smart Combiner Boxes: Decentralized MPPT for Enhanced Control

The alternative is rather than having the MPPTs in the inverters is to put them all into the combiner boxes and use intelligent control to run each at the MPP for the string to which it is connected. Typically, there will be between four and eight MPPTs in a combiner box.

Precision Current Measurement with LEM’s Current Transducers

To measure the current, the MPPTs either in the string inverter or the intelligent combiner boxes will use such a product as the HLSR from LEM. This measures the current inside the DC-DC converter so it can perform the MPPT function. These can be used in both the string inverters and in the intelligent combiner boxes.

These HLSR current transducers are the state of the art. They provide the best accuracy of around one per cent and have a 2μs reaction time, which is fast enough for the 50kHz switching frequencies. They also have a robust design, which means they can withstand lightning strikes – they can withstand 5 to 10kA for 8 to 20μs pulses.

And their isolation suits 1500V designs, the level at which most large plants run or are aiming to run.

Finally, the HSLR is the most simple, reliable and efficient transducer in the market. It is made from LEM’s proprietary ASIC, which has been specially designed and optimised for open-loop current transducers. Every step of the production process was optimised to support the inverter manufacturers with the huge price pressures they face. The HSLR is the way to create more efficient, better quality and lower cost MPPTs.

For demanding users, LEM also offers the HO series that, in addition to the HLSR features, provides an additional OCD output. This digital output indicates that the current has exceeded a defined threshold of typically three IPN. It can be used as hardware protection for the transistors, reducing the component count and the complexity of the design.

Fig. 1 shows the basic diagram of an MPPT controller and describes the HLSR and HO functions.

Smarter Measurement for Smarter Solar Farms

As energy costs increase and governments offer incentives for increased use of renewable energy, this has led to utilities building large solar farms. The solar market grew 25 per cent to 55GW in 2015 and is expected to exceed 70GW in 2016. This has created with it a push to increase the efficiency of how the power is captured from these sources. With these large solar farms, the improvements in power electronics mean it is now viable to use more MPPTs so that each part of the plant can run at its maximum efficiency.

However, to do this, accurate ways of measuring the current are needed and so it is important to use the latest designs of current transducers such as the HLSR series from LEM. In that way, whatever the weather, utilities will know they are getting the best out of their solar farms.